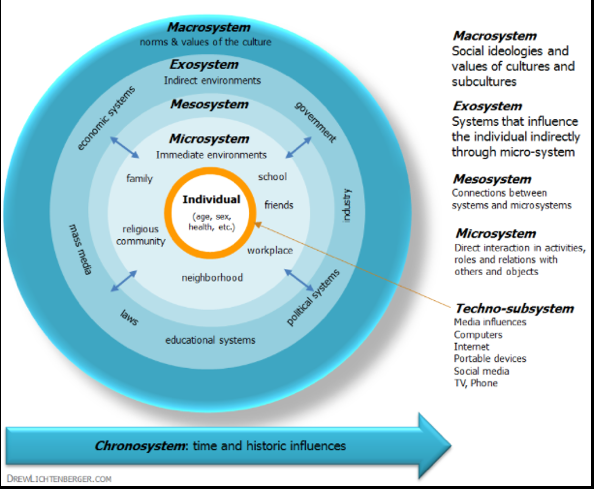

Proximal processes refer to sustained

interactions between a developing organism and the persons, symbols,

and activities in its immediate environment. To be effective,

these processes must become progressively more complex and interactive

over time.

|

Urie Bronfenbrenner's Bioecological Model Of Development (WIKI))

|

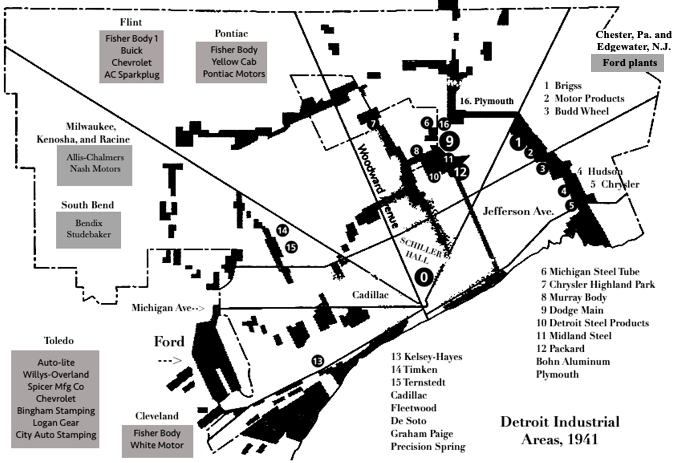

Proximal processes

are at the heart of figure 1 and figures 4 a and b. The concept of proximal processes represents an invaluable further

advance in our understanding of the development of situated organisms

(not Cartesian selves), and a further development of the thinking

associated with Vygotsky (ZPD: Zone of Proximal Development). The

excerpt from Ceci (On Intelligence)

provides a conceptual framework for interpreting a variety of texts,

interviews, videos, etc. wherein can be seen these very processes

unfolding. The article by Bruner is included because there is a

tendency among my Vygotskian associates to see Piaget as somehow

antithetical to Vygotsky. Bruner provides a necessary

corrective. Genovese and Orton show how useful Piaget’s work

remains, despite the justified criticism of its ahistorical, Cartesian

character. Franzos (“Schiller in Barnow”) and Munro (“Family Furnishings”) are works of fiction. In "Schiller in Barnow" Franzos shows "how, in the spirit of Enlightenment universalism, a love of Schiller brings together members of three oppressed groups: the Jew Israel Meisels, the unhappy monk Fransiscus (a victim of clerical tyranny), and the Ruthenain schoolmaster Basil Woyczuk. Their favourite Schiller text, appropriately, is the 'Ode to Joy' . . . with its appeal to all humanity to join in an embrace." Intro, p, 111 Alcorn's Narcissism and the Literary Libido is an incredible study that takes us into the heart of Figure 1, Bildungsproletarians and Plebeian Upstarts. Schiller Hall in Detroit should be viewed as a radical salon. Munro, on the other hand, provides a portait of a deadly, stultifying existential domain (the dinner table). There are millions of such deadly proximal zones, where the potential for cogntive development is crushed. The Sunderland and Johnson videos provide isights into two such Proximal zones: everywhere. Something is happening to cognitive performativity (which always includes the arenas and purposes of such performativity, as well as context  and audience) more broadly in the United States. It is not just Donald Trump who talks like a fourth-grader. and audience) more broadly in the United States. It is not just Donald Trump who talks like a fourth-grader. |

|

Proximal Processes Stephen J. Ceci, On Intelligence: A Bioecological Treatise on Intellectual Development (Harvard, 1996) .

. . it is time to ask about the nature of the resources responsible for

intellectual growth. . . . . In a recent article Uri

Bronfenbrenner and I proposed specific mechanisms of

organism-environment interaction, called proximal processes, through

which genetic potentials for intelligence are actualized. We

described research evidence from a variety of sources demonstrating

that proximal processes operate in a variety of settings throughout the

life-course (beginning in the family and continuing in child-care

settings, peer groups, schools, and work places), and account for more

of the variation in intellectual outcome than the environmental

contexts (e.g., family structure, SES, culture) in which these proximal

processes take place. Proximal processes refer to sustained

interactions between a developing organism and the persons, symbols,

and activities in its immediate environment. To be effective,

these processes must become progressively more complex and interactive

over time." 244-5 Jerome Bruner (1997), "Celebrating Divergence: Piaget and Vygotsky," Human Development, 40(2), 63–73.Jeremy E. C. Genovese, "Piaget, Pedagogy, and Evolutionary Psychology" (Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 1, 2003) from Anthony Orton, Learning Mathematics: Issues, Theory, and Classroom Practice (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004) Nevertheless, the

terminology 'concrete operations', 'formal operations', is still

apparently found to be useful by those reporting on empirical research,

and by many who write about child development and curriculum

reform. p.68

Marshall W. Alcorn, Jr., Narcissism and the Literary Libido: Rhetoric, Text, and Subjectivity (New York University Press, 1994) interview of Saul Wellman (CP Flint), Ciff Williams by Peter Friedlander Reginald Zelnick, Workers and Intelligentsia in Late Imperial Russia (University of California Press, 1999) John Dupré, "Causality and Human Nature in the Social Sciences," in Processes of Life: Essays in the Philosophy of Biology (Oxford, 2012) Garrison to Frankfurter (Allis-Chalmers) Interview of Cliff Williams S.A. Smith, Revolution and the People in Russia and China: A Comparative History (Cambridge University Press, 2008) Mark von Hagen, Soldiers in the Proletarian Dictatorship:the Red Army and the Soviet Socialist State, 1917-1930 (Cornell, 1990) |

from the Ed Lock (CP, UAW Local 600) interview

|

from the Ed Lock (CP, UAW Local 600) interview: I was very active in MESA --- Ford in USSR petered out in March of 1933, and I was laid

off. Several months later I found employment in a job shop as a

milling machine operator. I got signed up in the MESA, that was a

unionized plant. The job didn't last long.

In that period I would hang out at the MESA hall, Schiller Hall on Gratiot Ave. . . It was very much a Left hall. I became very interested in union . . . I was very young, 20 yrs old. My father was AFL, a ship carpenter, but I didn't assimilate much from him. But I became very interested in the MESA, and one of the characteristics of the time was that large  numbers of radicals of all descriptions IWW, Communist, Socialist . . .

would come to this hall, and we would sort of sit around and have big

bull discussions with the old timers from the IWW and the Communists

and whoever was there . . . We would all participate in these

discussions, each of them would bring their literature round . . . I

got involved so to speak, I was unemployed, but I would still go

because I found these meetings fascinating, and I would participate in

the distribution of leaflets.

numbers of radicals of all descriptions IWW, Communist, Socialist . . .

would come to this hall, and we would sort of sit around and have big

bull discussions with the old timers from the IWW and the Communists

and whoever was there . . . We would all participate in these

discussions, each of them would bring their literature round . . . I

got involved so to speak, I was unemployed, but I would still go

because I found these meetings fascinating, and I would participate in

the distribution of leaflets.I would go out with some of the leaders, and go with John Anderson or John Mack, who was a leader at that time. I went to--not so often to Fords--but I went to the Cadillac plant, Ternstedt, places like this, and GM, and would distribute organizational . . . I got involved in the Detroit Stoveworks strike . . . The MESA had undertaken the organization there and had a bitter strike there. A matter of fact I had guns put in my ribs in this strike threatening to kill us. But this was part of my education in the trade union movement. |

Janice Sunderland

Alice Munro, "Family Furnishings," in Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014 (Knopf, 2014)

On Becoming Communist: Flint, Michigan circa late 1940s

|

Wellman:

Flint is what I consider to be the asshole of the world; it's the

roughest place to be. Now we recruited dozens of people to the

Party in Flint, and they came out of indigenous folk. And those

are the best ones. But we couldn't keep them in Flint very long,

once they joined the Party. Because once they came to the Party a

whole new world opened up. New cultural concepts, new people, new

ideas. And they were like a sponge, you know. And Flint

couldn't give it to them. The only thing that Flint could give

you was whorehouses and bowling alleys, you see. So they would

sneak down here to Detroit on weekends--Saturday and Sunday--where they

might see a Russian film or they might . . . hear their first

opera in their lives or a symphony or talk to people that they never

met with in their lives.

SW: but you lose them in their area . . . PF: right. You lose them, but I think something is going on there that I think radicals have not understood about their own movement . . . SW: right . . . PF: something about the urge toward self improvement . . . SW: right . . . and cultural advancement . . . SW: right, right . . . PF: and not to remain an unskilled worker in the asshole of the world . . . SW: right, right. But there are two things going on at the same time. The movement is losing something when a native indigenous force leaves his community. On the other hand the reality of joining a movement of this type is that the guy who is in the indigenous area looks around and says this is idiocy, I can't survive here. |

from the Joe Adams interview re. militant secularism: all these guys, reuther (later visiting churches)

Carl Husemoller Nightingale, On the edge: a history of poor black children and their American dreams (Basic Books, 1993)

Zena Smith Blau, Black children/white children: competence, socialization, and social structure (Free Press, 1981)

Jack Katz, Seductions of Crime (Basic Books, 1988)

Bildung 2020

Williams

Lock